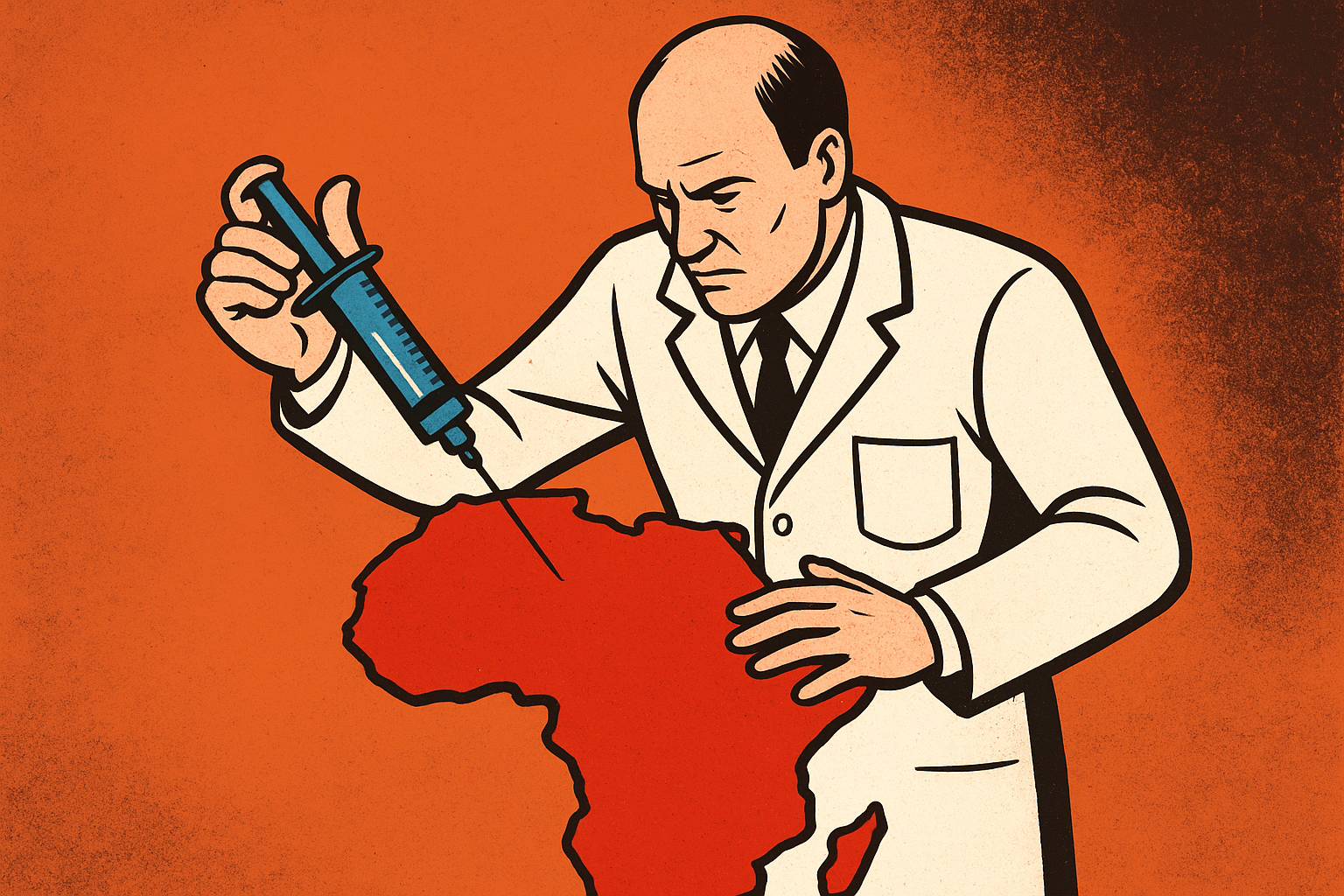

News recently broke about the world’s first 8-year contraceptive being introduced in Kenya, supported by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. This initiative, part of broader Africa contraceptive trials, is set to expand to other African countries. On the surface, this seems like a breakthrough: longer-lasting, more effective birth control options for women who want them.

But beneath the headlines, serious ethical and historical questions demand attention.

Why Africa? A Pattern of Vulnerable Populations as Test Subjects

Why is Africa chosen for these trials, instead of Europe or North America, where reproductive health challenges also exist? Why are African women, particularly Black women, so often selected as test subjects for experimental medical interventions?

This concern isn’t unfounded. History provides sobering examples. The Tuskegee Syphilis Study in the United States left hundreds of African American men untreated in the name of science. In the 1990s, Pfizer’s drug trial in Kano, Nigeria, caused child deaths and long-term disabilities. These incidents reflect a disturbing pattern: vulnerable communities are often treated as testing grounds for powerful institutions.

The Gates Foundation Perspective: Challenges in Africa

The Gates Foundation highlights Africa’s unique challenges: high fertility rates, limited access to contraception, and strained healthcare systems. These points are valid. But providing solutions is different from exploiting vulnerability. Why not first test long-term contraceptives in high-income countries, where oversight is stronger and volunteers can make fully informed decisions?

Population Control Narratives: A Troubling Lens

Critics argue that Africa is often seen less as a partner in development and more as a demographic “problem” to manage. This perspective risks reducing millions of lives to statistics rather than respecting individual agency.

Let’s be clear: family planning is essential. Contraceptives save lives by preventing unsafe pregnancies, and many African women want better options. Yet power dynamics become concerning when Western institutions primarily develop, fund, and test these solutions.

Ensuring Ethical Rollouts: Transparency and Local Leadership

As the rollout begins, transparency and ethical safeguards must be prioritized. African governments, civil society, and health advocates must ensure that this initiative truly serves African women, not just the agendas of wealthy foundations.

Because history shows one painful truth: when vulnerable populations become testing grounds, the powerful rarely bear the cost.